The handcrafted Neapolitan Nativity Scene in terracotta.

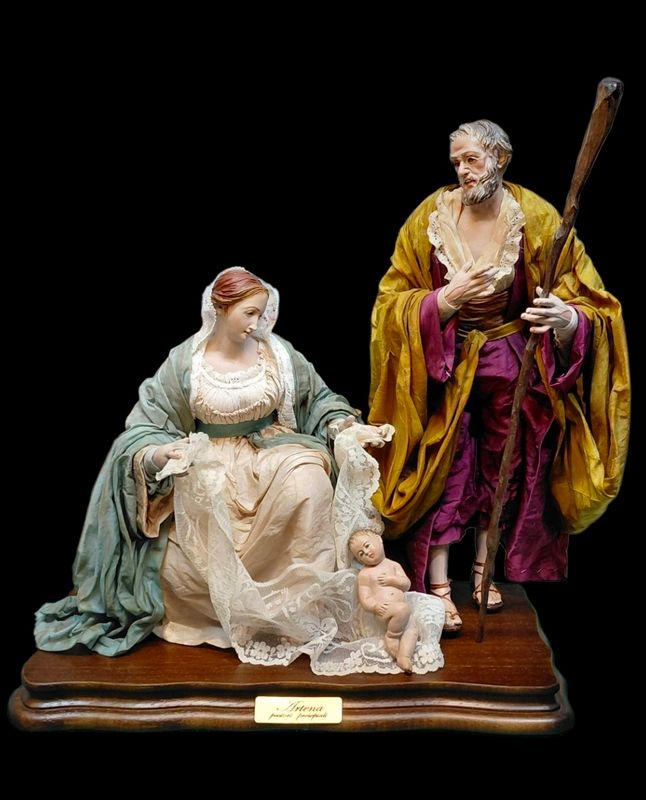

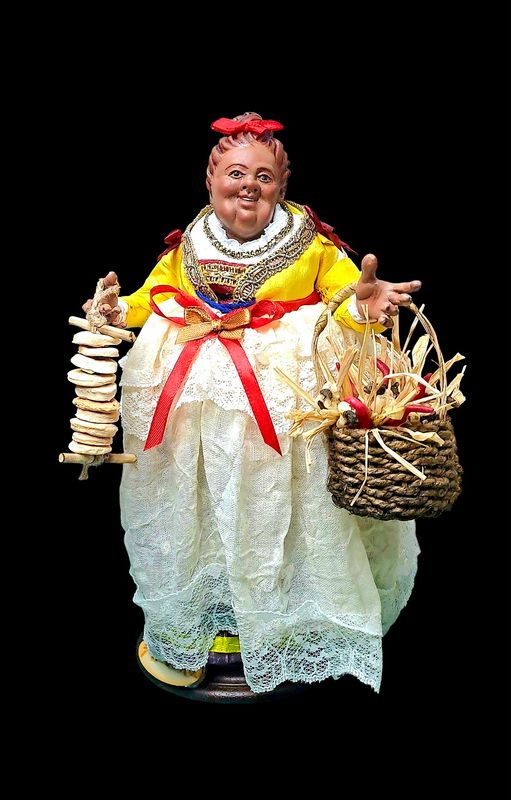

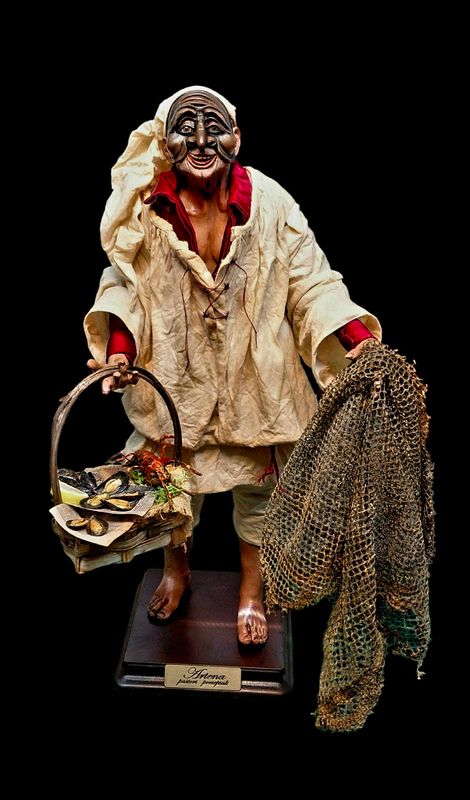

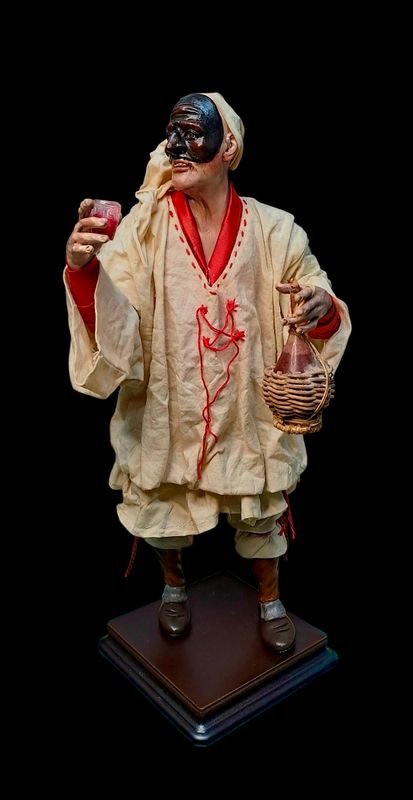

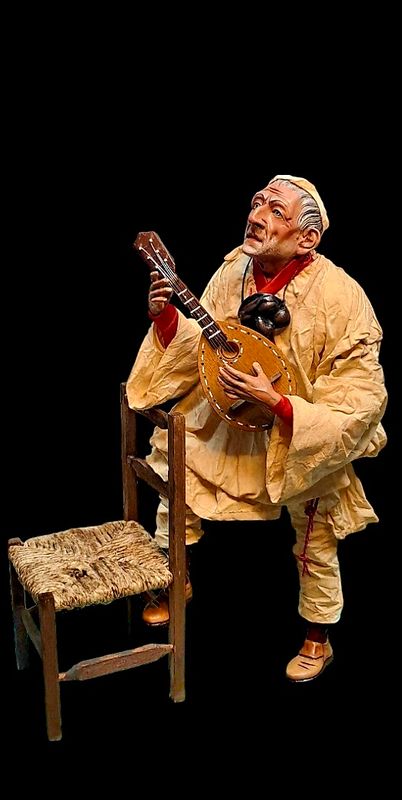

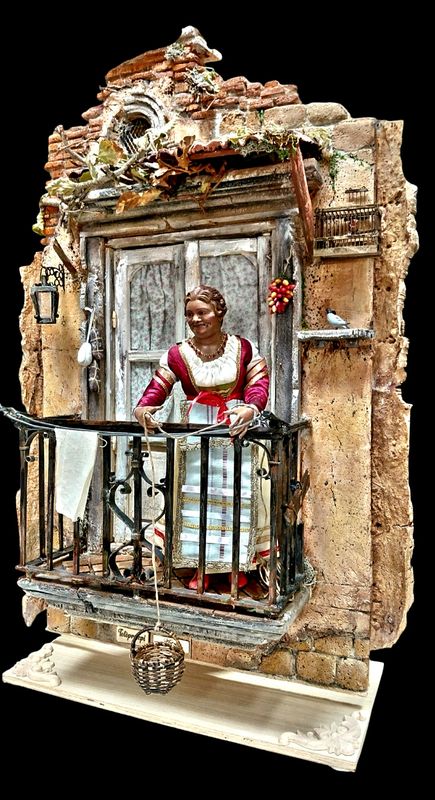

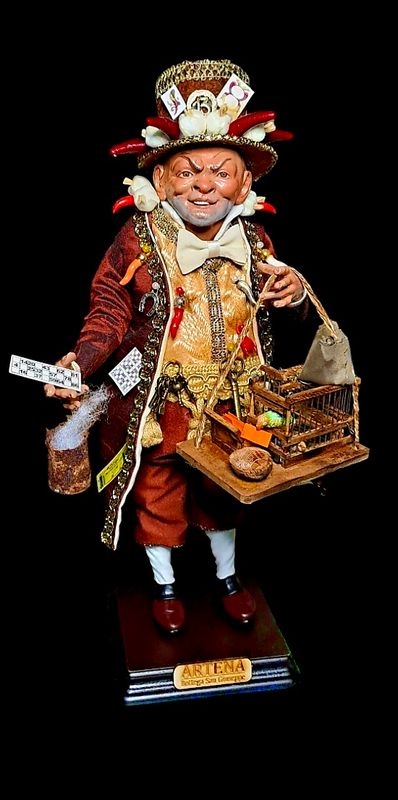

Artena creates handcrafted Neapolitan shepherds in terracotta and Neapolitan nativity scenes entirely handmade according to 18th-century tradition. Each nativity figure is created in Vincenzo Fortunato's workshop using historic techniques: terracotta heads, hands, and feet, glass eyes, wire cores, and molded hemp bodies. The Artena collection includes nativities, shepherds, Pulcinellas, Munaciellos, Bella 'Mbrianas, figures, crafts, and nativity scene settings from the Neapolitan tradition in 18th-century style. Unique works intended for collectors, enthusiasts, and lovers of Neapolitan nativity art. Discover Artena's handcrafted Neapolitan shepherds and terracotta creations, handmade in Italy.

Featured Products

Display prices in:EUR